Philadelphia Leadership: Jane Golden, Founder and Executive Director, Mural Arts Philadelphia

Jane Golden, Founder and Executive Director of Mural Arts Philadelphia, spoke with PHILADELPHIA Today about growing up in Margate, New Jersey, where she fell in love with the ocean and art. She took art lessons from a young age and discovered a competitive streak when she entered her paintings in competitions.

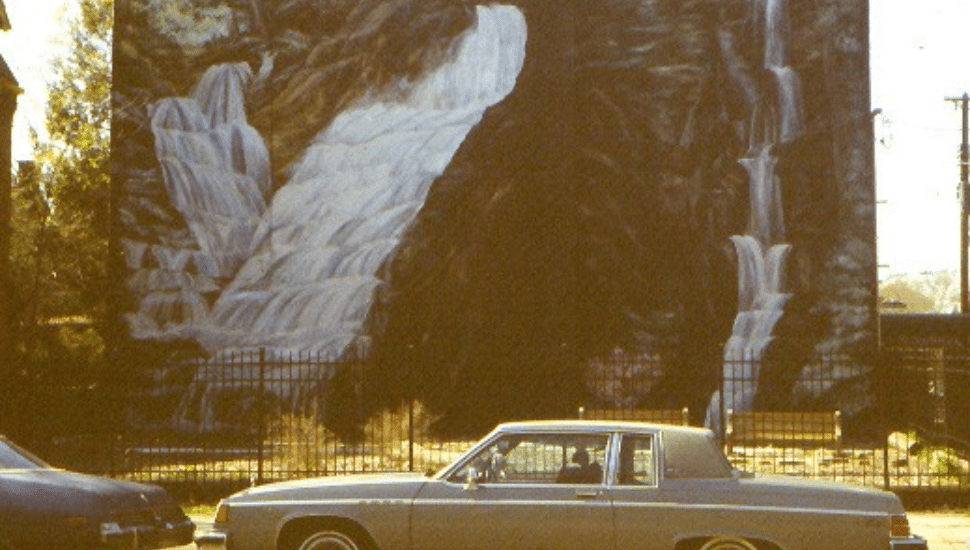

Golden also recalled living in L.A., “the center of the mural universe.” When she moved back east, she heard about Wilson Goode’s Anti-Graffiti Network and immediately got involved. A decade later, she founded Mural Arts Philadelphia, which creates hundreds of community murals throughout the city and works with young people and marginalized groups such as homeless and formerly incarcerated people.

Where were you born, Jane, and where did you grow up?

I was born the oldest of two children in Minneapolis, but my parents moved to Ventnor and then to Margate, N.J., when I was four or five years old.

What did your parents do?

My mom was a gifted watercolor artist. My dad was a businessman, and he ran a chain of stores called the China Outlet and the Gourmet Garage. He had a populist sensibility about retail and believed that people should be able to get great things at a very discounted price.

What do you remember about growing up in Margate?

The most vivid memories I have are of being close to the beach. I had a view out of my window of the ocean that was so beautiful, and we would walk on the beach year-round. In the summer, I surfed. We had a sailboat. We had a skimboard. I would ride my bike down to Longport. This is before Margate became what it is today, which is rather affluent. It was a very family-oriented place.

Did you have any jobs when you were growing up?

Yes, I always had a job. I worked at Camp By the Sea for a number of summers. At first, I was a Junior Counselor, and then I was an Assistant to the Arts and Crafts Counselor.

One summer, I worked on the boardwalk and sold wallets, but I didn’t like that job at all. It was very boring. And one year, I assisted somebody who made the floats for parades at the shore.

I was pretty industrious, and I always took art classes. I had classes with a watercolor painter named Miriam Jameson. I always entered the boardwalk art show, and I was a very poor loser. If I didn’t get a ribbon, I was just mad as can be.

Where does that competitive streak come from?

I’ve always been competitive since I was young. I think my parents had high expectations. They were wonderful parents, but they were very clear that if I wanted to play piano or do artwork, I needed to be serious and work at it. I started doing art at 10, and I continued with it all my life.

What lessons did you learn from those jobs that influence how you work today?

I always felt like I had to be responsible and pay attention to detail. My parents infused in me a degree of rigor, so I brought that into the job. They also taught me that even if you had a job you didn’t particularly love, you should finish it. Even the store on the boardwalk that I really didn’t like — my parents encouraged me to finish out the summer. I think that built in me a sense of grit or tenacity that has been useful my whole life.

Did you play any sports when you were young?

I played tennis, and I swam some. When I was growing up, sports were not as big as they are now. I surfed and sailed a little. Growing up there, the sound, the smell, and the feel of the ocean was so alluring that I immersed myself in that direction rather than regular athletic pursuits.

You can’t have grown up when we grew up without music. What kind of music floated your boat?

I love Motown. I also listened to Simon and Garfunkel and Cat Stevens. I remember going to a Leon Russell concert, and there were always concerts in Atlantic City at different piers. Whenever I hear oldies, like Jerry Blavat’s show on WXPN, it makes me think of the shore.

Where did you end up going to college, and why there?

I went to two schools. First I went to Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. Then, I was apprenticing with a very well-known artist in New York City, and through him, I met the head of the Art History department at Stanford University. I was going to transfer because I wanted an art program with more of an emphasis on painting, and he said, “You should apply to Stanford.”

I worked hard to hone my portfolio, and I got in and fell in love with Stanford. There were incredible art teachers and very small classes. And the physical beauty of that part of the country took my breath away.

How did you ever leave California, given that beauty?

After I graduated, I moved down to Los Angeles because I had friends there. That’s when I started to paint murals. At this period in time, L.A. was the center of the mural universe. I applied to an L.A. mural program called Spark, and I got a small grant.

Who saw promise in you in college and early in your career?

My parents saw that I loved art, and they saw some potential and encouraged me. My art teacher, Mrs. Jameson, also saw that, and she encouraged it.

And when I was at Mount Holyoke, I took a class with a very well-known realist painter named Alfred Leslie. I learned from him what it meant to be a serious artist. He, at first, was very hard on me, but it made me a better artist and a stronger person.

In the summer, twice, I took a painting workshop at Tanglewood, and the professors were very, very hard. It was like, “Buck up. This is life. You have to improve.” So I did. I just hung in there. It made me confront what I could and could not do. If you confront your limitations, you can choose to push past and try, or you say, “I’m going in a different direction.”

So, how did you get from L.A. to Philadelphia?

I painted a number of murals in Los Angeles. I formed an organization where we worked with kids on probation. My friends and I also did private commissions to make extra money. I was an Artist in Residence for the city of Santa Monica, and I had a job working in the city of L.A. I was the Assistant on a 10-story mural there.

But then I started to get very sick. I couldn’t move my hands. I just didn’t feel well at all. I went in for some tests, and I got a lot of inaccurate diagnoses, and then I got sicker.

Eventually, I was diagnosed with lupus. I was in the hospital for a period of time, and then I came back east to be with my family. I was coming up to Philly to Hahnemann Hospital for treatments, and that’s when I started to read about Philadelphia. Mayor Wilson Goode was starting this anti-graffiti network. In one of the articles, he said he was going to hire someone to create an art division for kids. I sent him my resume and a letter.

About three weeks after I sent the letter, I got a call from a man named Oliver Franklin. He was the Deputy City Representative for Arts and Culture. He said, “I’m a good friend of Judy Baca,” who was my first boss in L.A. He said, “I asked Judy if I should hire you. She said, ‘Jane Golden will drive you crazy because she’s so tenacious. But you should definitely hire her.'”

How old were you at this point?

I was pretty young, maybe 28. I was interviewed by Oliver and then by Tim Spencer, who ran the Anti-Graffiti Network. Tim hired me on the spot, told me I would be making $12,500 a year, and then informed me he didn’t have a desk for me to work at!

I founded Mural Arts in 1998. I worked for Anti-Graffiti from 1985 through 1996. During the time off when I was trying to figure out what I would do, I thought I would go to law school. I was a double major in Political Science and Art. But my brother’s a lawyer. He said, “I don’t think you want to go to law school. I think you should run an art program for the city.” I said, “There isn’t one.” And he said, “Well, go start one. Go talk to Ed Rendell.” And that’s exactly what we did.

So, here we are in 2024. We’re a quarter of the way through the year. What are you focused on? What are your priorities, Jane?

One is to make sure that our programmatic areas are healthy and running in the most robust, fashion possible. We work in different areas. We work with art education, where we serve 2,500 young people ranging in age from 11-18. We’re honing our entrepreneurial program so kids can get real-world experience and know that if they have an idea, we’ll help them take it to fruition.

We have the Porch Light program, and that’s our partnership with the Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services. We’re working with people grappling with trauma, substance abuse disorder, housing insecurity, mental health issues, and immigration. It’s beautiful, important work.

We have a same-day work program called Color Me Back, where we pay people for a morning’s worth of work. We bring in career links and social services, and people are beautifying Kensington. And we’re partnering with SEPTA and beautifying the concourse.

In our restorative justice program, we work with people in the state prison and people coming home. These are young adults, ages 18-24, who have been either on probation or coming out of the system.

We’re giving small scholarships to young people who are coming home and giving them support so they can pursue an artistic career. And in our reentry program, we have a very low recidivism rate and a high percentage of people going on and getting employed.

And we do community murals all over the city. Last year we created 147 murals. So, I’m proud, and I want to make sure we stay on track to bring art to every single neighborhood of Philadelphia. I think art is like oxygen. And I think it’s fantastic that we’re in a city where the murals are like the autobiography of the city of Philadelphia.

So, what do you do with all that free time that you have?

Well, my second job is teaching at the University of Pennsylvania. I’m an Adjunct Instructor. I teach an interdisciplinary class called “The Big Picture” about how we use art to better understand the city and its problems and help us find solutions. And I am a Critic-in-Residence at a school in Baltimore, the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA).

What about hobbies?

In my spare time, I’m a voracious reader. My favorite Author is Joan Didion. I love the way she captures life and the way she writes about California. I go for walks with my husband and our dog, and I like to bike sometimes. In the summer, we try to take some time and go to the shore.

Three last questions for you, Jane. What’s something big that you’ve changed your mind about over the last 10 years?

Two things, I think. We’ve worked in Kensington for 10 years, and we had a storefront where we were working with people struggling with addiction. It didn’t start out that way, but it was such a crisis in Kensington, and we felt an imperative to serve whoever was there. We brought in nurses and social workers. But we became very immersed in this world and lost sight of what the greater community needed. We started to get a critique from neighborhoods that said other people wanted mural art services too. Also, the question was raised if we being soft on people who were drug-addicted.

At first, I was defensive. But we made a pact to really listen to the neighbors, and it started a path of reconciliation and new work that we hadn’t expected and partnerships and collaborations that were fruitful and generative. We’re still serving those who are vulnerable in Kensington. And we’re equally as responsive and attentive to the neighbors who’ve been there for a long time and who have seen their neighborhood struggle. The work we do is really humbling; it demands a certain amount of patience, respect, and grace. The rewards are great, but the path is often complex.

The other thing is that in the restorative justice work that we do, there was a moment about eight months ago when we had to make some hard decisions. It was hard to look inward and course-correct. We were involved in a mural project where we had tapped into racism in a part of the city, and it became a very divided project We had to hire a mediator, a Quaker mediator, who brought all of us together. Eventually, over time, we were able to negotiate a compromise.

What keeps you optimistic, Jane? It’s a crazy world out there.

I’m optimistic when I see the passion of the young artists we work with and how they see the world through their eyes of hope and possibility. I’m also optimistic when looking at our Guild Re-Entry Apprenticeship Program and seeing how the people in this program have learned new skills. They’re so excited to bring a work of public art to life that will be seen by many city officials.

I’m hopeful about our new mayor and the way she talks about the city. When I talk to Carlton Williams, who’s heading Clean & Green, I feel his sense of optimism, and that’s contagious. While it’s a complicated path, there are pockets of hope that happen almost weekly.

Finally, Jane, what’s the best advice you’ve ever received?

A really interesting piece of advice came from a Professor at Stanford who came to see me in L.A. I had applied to be in a couple of group shows and had gotten turned down. He said, “Just take pleasure in drawing and seeing and creating, and keep doing that over and over again.” That felt like a breakthrough to get his blessing to free myself from these expectations around galleries and museums.

The other good advice I got was from a former President of the Ford Foundation, who I had gotten a grant from. She said, “You’re trying to do everything. You need to limit your scope, think about what you’re good at, and go deep.”

The other advice came from Estelle Richman, who was the Health Commissioner under Ed Rendell, Director of Social Services and Managing Director under John Street, who eventually went to work for the Obama-Biden Administration. Her advice to me was to use art on behalf of the citizens of the city in a way that was both aspirational and highly pragmatic. She showed me that you can strive for beauty and awe and, at the same time, look at bottom-line things that citizens are dealing with.

Finally, my dad advised me to always have humility and to be gracious and grateful. That was such great advice because we only know what we know. We don’t know what we don’t know.

Connect With Your Community

Subscribe for stories that matter!

"*" indicates required fields